The historical setting

Water was created first, life and land were created next, land promised to take care of all life, all life promised to take care of the land.

A long time ago the Indian people also promised to protect the land and have the responsibility to care for her. Water represents an integral link in a world view where water is sacred and extremely important in preserving precious balance. Water is the origin of and essential for the survival of all life.

The Columbia River System encompasses over hundreds of thousands of miles of streams with over a billion cubic feet per second a year passing along its shores into the Pacific Ocean. The system reaches deep into the interior of North America and drains over 259,000 square miles. The river flows from sources in the North American Rockies, from mountain sources along Snake River including the middle Rocky Mountains, from both sides of the Cascade Mountains, and flows through estuaries to the Pacific.

Due to the cool clean water from many different sources the environment of the Columbia Plateau region produced abundant and diverse natural resources.

The numbers of salmon, lamprey, steelhead, sturgeon and other fish were infinite. The fisheries were the staple of all life on the Columbia Plateau.

Eagles, Bears, Coyotes, Cougars and Indians were amongst those who relied on the Salmon. Elk, deer, antelope, and many other smaller mammals were abundant. The rivers and streams abounded with beaver and otters, seals and sea lions were known to venture up the Columbia River to the great fisheries at Celilo.

Several kinds of grouse, quail, and multitudes of geese and ducks as well as hawks, owls, badger, rabbits, and other wildlife shared the diverse wetland, steppe, desert, and upland .

Roots, nuts, berries, mushrooms, medicine, food, and fiber plants were seasonally available during the year. The hillsides were covered with lush bunch grasses, the timbered mountains were healthy, natural wildfires and floods were part of the cycle, the river vegetation was lush, and the water was cool and clean.

The conditions were pristine and wildlife was naturally abundant. Survival was not easy for Indian people but the tools and resources were available to support Tribal life since time immemorial.

Our ancestors' way of life

Salmon, Huckleberries, and other resources were gathered seasonally. As with most foods the huckleberries had to be dried for future or winter use. Dried berries, roots, onions, nuts, herbs, spices, mushrooms, meat and fish would be dried and cached for later use.

Foods would be dried individually or sometimes would be mixed and pounded to form cakes for storage. The hunting, gathering, and procurement of food and raw materials for tools was the order of the day.

Living not only required a supply of raw material and food; an organizational strategy and an efficient disciplined skilled source of labor was required to ensure survival throughout the year.

Fish were dried and pounded into cakes and packed into baskets for winter subsistence or commerce. Tribal fishermen would harvest from several different salmon runs occurring during different times of the year.

Many tribal members would move toward the Columbia and its main tributaries during the fishing seasons. Fishing was the primary means of livelihood and survival for Tribal members. The conditions along the Columbia and Snake River systems were so good that all that was required for a fisherman was a dip net, gaff hook, small spear, or a hook and line depending on where and what season they were fishing. Salmon ran during spring, summer, and again into the fall. Some Tribal members would stay at their usual and accustomed sites for the whole season others for the entire year.

Many tribal members would move toward the Columbia and its main tributaries during the fishing seasons. Fishing was the primary means of livelihood and survival for Tribal members. The conditions along the Columbia and Snake River systems were so good that all that was required for a fisherman was a dip net, gaff hook, small spear, or a hook and line depending on where and what season they were fishing. Salmon ran during spring, summer, and again into the fall. Some Tribal members would stay at their usual and accustomed sites for the whole season others for the entire year.

The extensive and productive fishery allowed some Tribal people lived on the Columbia River year round. As seasons permitted some Tribal people would head into the mountains to hunt and gather plants, medicines, and other resources and again to fish in the tributary headwaters.

Columbia river people accessed the region through the river system by canoe and travel into the mountains was on foot sometimes relying on dogs to help pack the load.

There were specific spiritual and practical preparations that had to be adhered to ensure prosperity and subsistence. It required a diverse cultural system, with rules and a specialized division of labor to ensure survival. Without strict adherence to many of those cultural traditions survival for over 13,000 years would not have been possible.

The entry of Spring on the Columbia Plateau with the arrival of fresh plants and the dramatic return of the Salmon are reaffirmed annually, year after year. First food feasts gather the Tribe to celebrate the renewal of life cycles together with their community.

Spiritually, the Tribes do not separate themselves from the surrounding natural world. Individuals have a personal relationship with the Creator through the sweathouse and individual Weyekin. Larger groups reinforce this personal relationship with the land and the Creator in the long house. The longhouse is the community center where Indian people come together as a community to practice religion, to mourn, to socialize, and to celebrate the occasion.

Water is honored first at the feasts. Individual faith is also practiced on a personal level such as through the sweathouse. The sweathouse is utilized to communicate with the Creator, for medicinal purpose, as well as to build of one's physical and spiritual strength.

The winter on the Columbia Plateau was often hard and severe. Careful preparation for winter was crucial for survival until the spring. Social discipline, responsibilities and roles of men, women, children and elders were maintained and reinforced through daily educational experiences such as ritual, relationships, food and resource procurement, and language.

Youth learned from elders and were encouraged in the many skills required. Extended family relationships were known by all, as well as where one's people originated from, their number, character, and abilities. Indian names were given based on individual attributes. Indian names also reflect the history and ancestry of the Tribes with names reflecting past leaders, special events, or even places.

Elders remind us that there did not used to be Tribes as we know them today, Indian people were identified as so and so's people, were recognized by their family, or by where they come from.

Survival was depended on working with each other as one elder reminds us; "Indians used to help each other. In the old days there was no welfare or aid. If someone was down people would help them."

People of the lower Columbia

The Walla Walla and Umatilla are river peoples among many who shared the Big River (Columbia). The Cayuse lived along the tributary river valleys in the Blue Mountains. The Tribes lived around the confluence of the Yakama, Snake, and Walla Walla rivers with the Columbia River.

The river system was the lifeblood of the people and it linked many different people by trade, marriage, conflict, and politics. The people fished, traded, and traveled along the river in canoes and over land by foot.

The Walla Walla, were mentioned by Lewis and Clark in 1805 as living along the Columbia just below the mouth of the Snake River as well as along the Yakama, Walla Walla, and Snake Rivers. The Walla Walla included many groups and bands that were often referred to by the village whence they originated from such as the Wallulapums and Chomnapums.

The Umatilla occupied both sides of the Columbia River from above the junction of the Umatilla River downstream to the vicinity of Willow Creek on the Oregon side and to Rock Creek on the Washington side. The river people were tied with other Tribes along the river with close family, trade, and economic interests in the Columbia River Gorge and the northern Plateau.

The Walla Walla and the Umatilla were a part of the larger culture of Shahaptian speaking river people of southeastern Washington, Northeastern Oregon, and Western Idaho.

The Cayuse, whose original language is known to linguists as Waiilatpuan, lived: "..south of and between the Nez Perces and Wallah-Wallahs, extending from the Des Chutes or Wawanui river to the eastern side of the Blue Mountains. It [their country] is almost entirely in Oregon, a small part only, upon the upper Wallah-Wallah river, lying within Washington Territory."

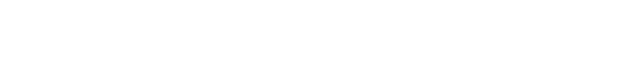

Prior to the horse the Cayuse were tributary fishermen. After the arrival of the horse and gun they sometimes were mounted warriors to protect their way of life. They lived throughout the lower Columbia Plateau from the Cascade to the Blue Mountains, and grazed horses on the abundant grasses of southeast Washington, the Deschutes-Umatilla Plateau. As horsemen the Cayuse had close ties to the horsemen of the Palouse and Nimipu.

The area from Wallula to the mouth the Yakama River where many members of the tribes lived could be considered the cross roads of the Columbia River System. This area was shared by many related bands and was a central hub of Tribal life on the Columbia Plateau.

Extended family relationships, social, and economic interests exists between many Tribal people from throughout the Columbia Plateau. The people on the Columbia Plateau were multi-lingual. Tribal members learned and spoke several trade jargons, other Indian dialects of Shahaptian, as well as, Salish, Chinookian, and Klamath. Later they adapted to French and English.

The economy

Inter-Tribal relationships were based upon many needs key to the survival of Columbia Plateau life. Tribes throughout the region established relationships like any sovereignty, for military security and protection, trade and economic prosperity, education, religion, and family ties.

The Umatilla, Walla Walla and the Cayuse were very influential within the region in economics and politics of the Plateau due to their key geographical setting, halfway between the Pacific Coast and the Great Plains.

The Umatilla, Walla Walla and the Cayuse were very influential within the region in economics and politics of the Plateau due to their key geographical setting, halfway between the Pacific Coast and the Great Plains.

The geographic setting also placed the Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Cayuse in the prime situation of being the middlemen of trade between the buffalo country of the Great Plains and rainforest and ocean resources of the Pacific Coast cultures.

Tribal members relied on trade goods from the plains such as buffalo meat and hides, obsidian from the south as well as abundant seafood, plants, and medicines from the Pacific Northwest coast.

Gatherings were held at many places throughout the region. Very large gatherings were known to be held and in the Wallula area near the confluence of the Snake River and at Wascopum near the ancient fishing grounds of Celilo Falls and Nine Mile Rapids.

Smaller gatherings were held in the many fertile river valleys in the region where peoples paths crossed during their seasonal round. At such gatherings many traditions such as language, religion, ritual, music, dance, legends, stories, feasts, sport, gambling, and families values were continued and passed on.

Perhaps due to the harsh realities of living close to the elements the Tribes created many forms of entertainment often involved risk. The Tribes on the Plateau enjoyed gambling and wagering on stick games, foot races, wrestling, hide races, horse racing, or other competitive feats. Wagers would include items of value such as raw materials, meats, fish, roots, berries, horses, slaves, finished products such as baskets, nets, bows, arrows and many other items of value. Risk was sometimes greater as a participant in some of the races if one was fortunate to be there to ride. The way of life and daily risk were such that the people developed a great sense of honor and humor.

Trade and barter was a significant aspect of Indian life on the Plateau and essential for the survival of Indian people. Indians relied on other Indians to provide goods they themselves were not able to obtain, were not available during their seasonal round, or not available in their country. Often groups from a single village community would travel different directions as part of their seasonal round.

Through years of trade relationships, elders new exactly what other Indians needed in exchange for goods they needed. The abundance of salmon in the Columbia and Snake Rivers and their tributaries gave wealth to the tribes who fished there. They dried and processed the salmon for their own subsistence and for trade to the other tribes of the Plateau and surrounding regions.

The vast grasslands and the mountains populated with game, roots and berries were wealth for those tribes who occupied them. To protect the regions abundant resources and their way of life it became necessary for the tribes to develop and maintain strong warrior traditions to defend the people, resources, and territory from their enemies. A strong warrior tradition helped to provide a foundation for defense and survival.

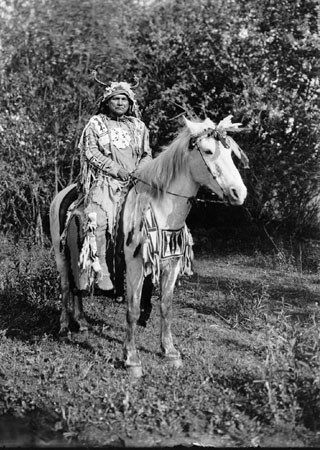

Life on the Columbia Plateau was recorded by the people in traditions and art. Songs, dances, and stories that embody the history of the Indian people are passed down generation to generation by oral transmission.

Life on the Columbia Plateau was recorded by the people in traditions and art. Songs, dances, and stories that embody the history of the Indian people are passed down generation to generation by oral transmission.

Stories and symbols were weaved into the many baskets, hats, and bags utilized by the people. Basketry evolved as a crucial survival tool and an art form. Elaborate balls of long hand woven string kept tract of many events of the peoples history. Rock art, cairns, and unique geological formations were present at many locations providing reference to the peoples lives. Personal histories are reflected through the individuals preparation of personal regalia and dance. Wealth was personal strength, family, community, comfort, and happiness.

Internal affairs

Individual abilities were recognized by elders at an early age. Headmen and chiefs were selected based upon their experience, abilities and skills. Elders were respected and often leaders had council with elders. Individuals were recognized for their spiritual strength, medicinal abilities, warrior qualities, recognized for their hunting and tracking abilities, fishing skills, art, weaving, education, discipline, healing, cooking or other skills. Labor and skills were divided as many survival skills were necessary.

Conflicts and issues were resolved by council of elders and leaders. Leaders were decisive when they believed that their followers had arrived at a consensus. If there was no consensus, powerful orations between the headmen and chiefs might soon swing the people on issues or problems of the day.

If an individual disagreed with the decisions of the band, he did not, nor was he forced to comply with the decision. Overall decisions of the Tribe were arrived at by consensus of the people. Planning and preparations were conducted in ways to prepare for future generations.

A very elaborate and complex Indian civilization once flourished on the Columbia Plateau. Resources were so abundant that the development of elaborate cultural material was not necessary.

Today Columbia Plateau social traditions have been maintained on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon, the Nez Perce Indian Reservation of Idaho, on the Yakama and Colville Reservations of Washington, at communities like Celilo Falls, and Priest Rapids. Many Tribes from the Columbia Plateau are related to one another by blood and marriage, linguistics, traditions, history, and religion.

Horses

Horses

The tribes owned a tremendous number of horses. The bunch grass covered hills of Columbia Basin was the home of the Cayuse and Appaloosa, as well as Pintos, Paints, and Mustang horses.

Due to the extraordinary amount of horses owned by the Indians living at the headwaters of the Umatilla the rugged Cayuse horse was identified with the people who have traditionally lived along the headwaters of the Umatilla River, on the foothills of the Blue Mountains. Appaloosas were bread for speed and ceremony by the Cayuse, Palouse, and Nimipu (Nez Perce).

The Cayuse Tribe was known for their large horse herds that grazed in the foothills of the Blue Mountains. Cayuse ponies were stout and able to move quickly through the steep and timbered Blue mountains Prestige and wealth was partially reflected by the number of horses that a person owned.

Tribal elders tell us that in those days the Indians had thousands and thousands of horses and that they needed areas for them to graze. There wasn't enough grazing area so they had to spread the horses out. The Cayuse used to graze horses all through the Umatilla Basin, across the Columbia River on the Horse Heaven Hills all the way to Hanford to the north, on the east side of the Blue Mountains from the Grande Ronde country all the way to Huntington, to the John Day River country in the South and all the way to the Cascades in the west.

The horse expanded Shahaptian and Cayuse culture, improved mobility and brought the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla into contact with other Indian cultures in Montana, Wyoming, Canada, California, Nevada, and throughout the Pacific Northwest. Horses increased the Tribes mobility allowing members to travel further, faster. Horses allowed for new ideas to be introduced from new places as well as allowing other Indians to travel and trade along the Columbia River.

While on the extended seasonal round, Indians would hunt elk, deer, and gather plant foods. Instead of packing resources themselves or by dog they would now dry meat and plants and pack them onto horses and move on to the next destination. They would go down to the river to trade and fish. If there was a surplus of food supplies and/or horses procured during the seasonal round the surplus would be used for trading to obtain desirable resources.

The external forces

History is often disregarded in today's fast-moving, technological society, but for the remaining Indian Tribes living in the United States, history is a reality that still greatly affects the lives of the people on the reservations.

The Treaty of 1855 and subsequent acts of Congress in the middle 1800's have directly impacted Indian economics, politics, social structure, and the individual lives of the Indians themselves.

The United States was a new nation during the late 18th century and early 19th century. Most of the world was being divided up amongst imperialistic European governments. By spouting right of religion, technology, and military might these nations were beginning to systematically claim land and lock up the new worlds natural resources for their needs, a practice that has continued into the 20th century.

Due to the political climate that imperialism created in Europe, the United States were able to buy a parcel of land that was known as the "Louisiana Purchase from the French." By the stroke of a quill pen "all Louisiana, from the gulf to the 49th parallel, and west to the Rocky Mountains, became the territory of the United States for the insignificant price of $15,000,000. "

Immediately thereafter, then President Thomas Jefferson, sent Lewis and Clark forward on a mission to explore the purchase and to strengthen the United States claims on the lands beyond the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific. Although the coast was explored early on the Pacific Northwest was still predominately unclaimed by European Nations, the French were there and Russians, Spanish, and the British were rapidly moving in, trying to claim the wealth of the regions resources.

Disease had already moved up the Columbia many times prior to the arrival of the Americans. By the time Louis and Clarke traveled the Columbia it was estimated that two different outbreaks of western disease had decimated the people living along the Big River. The Spanish reached the northwest coast as early as 1775 and the English in 1796. European contacts at the coast spread disease rapidly inland and disease claimed whole villages.

The inevitable reality was that the land was claimed by political circles beyond the scope of the Tribes. No government at the time doubted that resident Tribes had the superior military capability and controlled the region. Tribal peoples knew the land intimately and were considered as necessary and crucial allies by Euro-Americans. Without direct involvement with the Tribes, Euro-American interests could not compete with each other. Since the French and Indian War alliances with Indian tribes were highly desirable on political and economic levels.

The resources that Euro-Americans were first driven by were furs and salmon. Oregon was eventually nicknamed the Beaver State. Wealth in trade was furs and nothing was going to stop the interests competing for furs. Local native inhabitants were viewed either as necessary allies for exploiting a landscape foreign to the traders or as simply in the way. "The incentive of great gains in the fur trading business was a direct cause of the exploration and settlement of the Oregon Country."

Historically we should not undervalue the influence of the beaver as an international commodity and the impacts that procurement of such a resource had on the environment. Because of the immense value of its pelt we should not underestimate the greed of the entrepreneur or the impacts of such people on the environment.

The economic factor driving fur trading was the European and Chinese market demand for furs. The communities that were benefiting from the furs were far removed from the environmental impacts that their demands created.

The fur traders introduced new technological goods such as steel, knives, pot, pans, blankets, etc.. This was done to entice the Indians in the fur trade. The fur companies in fact had already established a long tradition of working with Indians to exploit their knowledge of the environment. Iroquois Indians employed by fur companies came to live in the Pacific Northwest. Fur traders, however, had to make local connections. "The Umatilla abounded with beaver, and the Indians were induced to trap this animal, as its skin could easily be sold to the white traders." The Tribes essentially became involved in the Traders competition for furs.

Early contacts between the Pacific Northwest Tribes and the white culture were initially economic in nature. Initially the Tribes viewed the goods and supplies that foreign traders and trappers offered as a welcome addition to their already thriving economy. Fort Nez Perce was established sometime around 1817-1818 as a trading outpost at the confluence of the Walla Walla and Columbia River. In 1835 it was renamed Fort Walla Walla.

The first explorers to the Columbia Basin were often amazed by the amount of natural resources that were present and were eager to exploit them. Indian regulation of trade was enforced by the headmen and chiefs. The Northwest Fur employees eventually abided by the rules set down by the Indians simply because of the control the Indians exerted over their neighbors and for locational and business purposes. Tariffs were levied against the trading post for incoming and outgoing goods by the leaders of the bands whose forts occupied their lands.

The missionary era

Contacts with the trading posts had initially introduced the Indian Nations to Christianity. This was done through British Protestants, and French-Canadian trappers who were for the most part of the Catholic faith.

The trappers were much impressed by the native religion in the area and found no conflict between Christianity and Native religion. Fur companies often encouraged their men to take Indian wives and marry into the tribes to strengthen trade relationships.

Protestant Missionaries had been in contact with Indians and some of the headmen in the region. The American Board of Foreign Missions in 1835, promised to locate missions in Cayuse and Nez Perce territories. In 1836, Dr. Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding arrived at Fort Walla Walla.

Whitman founded his mission with the Cayuse at Waiilatpu near Walla Walla, Washington. Spalding was assigned to convert the Nez Perce people and founded a mission at Lapwai, Idaho.

In 1838, two Catholic priests, Fathers Blanchet and Modesta Demers of the Diocese of Quebec, arrived at Fort Walla Walla to estimate the possibilities of beginning a Catholic mission in the territory. Saint Rose of the Cayuse was established near Walla Walla. In 1847 Father John B. Brouillett established a mission called St. Anne along the Umatilla River in a cabin donated by Chief Taawitoy.

In 1847, Dr. Whitman and his followers were killed by a band of Cayuse, along with some of their Umatilla, and Nez Perce allies. The reasons for this are many and varied but included:

- non-payment for property taken by the mission;

- increasing immigrations;

- Whitman's encroachment on Indian trade;

- fear of Whitman himself, whom the Indians believed had poisoned them; and

- the constant outbreaks of diseases introduced by Whitman and other non-Indians which had reduced the Tribe' s population by half.

Whitman claimed to be a doctor and preacher as well as being a missionary, merchant, and trader. In the Tribes tradition the failure of a medicine man was sometimes death, especially, when peoples lives were believed taken by that medicine man.

Differences in Indian and non-Indian values and attitudes set the stage for the so-called "Cayuse War" of 1847-1850. Actually, the "War" consisted of minor skirmishes with Cayuse-led war parties against the territorial militia and responses by the Oregon Territorial Malitia massacring any unfortunate Indian they stumbled across. The war parties were represented by mostly interior tribesmen who felt compelled to turn the immigrations back.

The war ended in 1850 when five Cayuses sacrificed themselves to stop the violence and injustice toward their people. They were convicted of killing Whitman and were hanged in Oregon City. They were essentially sentenced whether guilty or not to appease non-Indian concerns and fears.

The facts that Whitman was living on their lands by their customs, had not converted many Indians as a missionary, was believed to have brought disease to the Tribes and was encouraging non-Indians to take Indian lands never entered the case.

After the events at Whitman Mission the cabin was burned. It was almost two decades before the Catholic Missionaries returned.

Immigrants

The Oregon Territory and Columbia River Basin were enticing to those living in the over crowded East coast. Economic conditions for non-Indians were hard in the East. Most of the land was already owned and very expensive.

Enticing stories of the west including the Columbia Basin had made it into print on the East Coast, romanticizing the west as a "Garden of Eden" with unlimited resources. Such encouraged people to emigrate to the Oregon Territory.

"Passed by way of the Columbia river, the land along which is a mere collection of sand and rocks, and almost without vegetation. But a few miles from the Columbia toward the hills and mountains, the prairies open wide covered with a low grass of the most nutritious kind, which remains good throughout the year. In September, there are slight rains, at which times the grass starts; and in October and November, there is a good coat of green grass, which remains until the ensuing summer; and about June, it is ripe in the lower plains, and drying without being wet, is like made hay. It is in this state that it remains until the autumn rains revive it. The herdsman in this extensive valley of more than one hundred and fifty miles in width, could at all times keep his animals in good grass by approaching the mountains, on the declivities of which there is almost any climate; and the dry grass of the country is at all times excellent."

Early Euro-American occupation in the Pacific Northwest was extremely difficult and only fur traders and missionaries dared to make their way into the interior. The first wagon train into the Oregon Country was in 1843 however, successive waves of emigrants were to cross the United States on the Oregon Trail.

"Reports of explorers and fur traders aroused interests in the new frontiers promise of rich land and bounteous life." "In 1843 nearly 900 immigrants crossed the plains to the Pacific Northwest." "An estimated 1,200 settlers followed the Oregon Trail in 1844. The number swelled to 3,000 in 1845. The boundary line was approved by treaty in 1846 and from that time on immigrants knew they were settling in American territory." "The great tide of migration in 1847-an estimated 4,700 settlers coming into Oregon". (Meacham 1923)

Pioneer journals from the Oregon Trail mention meeting Cayuse families returning from buffalo hunting in the mountain valleys of Idaho. Quite often, the tribes traded their fine horses, and later their harvested vegetables, with the explorers and emigrants for cattle, clothing, blankets, and utility items. Their descriptions also alluded to the wealth of the land.

"...we are now traveling down the Umtillo river the indians hear has a great maney horses very fatt and the best I Ever Saw in my life they are very Rich som indians has from 50 to 100 horse and cattle in propostion they raise plenty of Corn and potaters and peas pumpkins squashes cabeges &c. this Countery is very fertile..." - Absalom B. Harden, Journal, 1847

The west at that time was very rough and hard on settlers from the east. The country was described as forlorn and formidable, a deep wild place. Two thousand miles and six months of hard overland travel or a long voyage by sea was required to get to the Oregon Territory.

Estimates from 1842 to 1849 indicate a total of 12, 287 immigrants moved through tribal homelands. The Indians' view of the immigration were mixed. The tribesmen saw the travelers as poor people moving through the country. Their horses and cattle were as exhausted as the immigrants themselves, who were often dirty and hungry. For the most part, both races viewed each other as inferior people.

Turmoil and the Treaties

Indian tribes were willing to live with the newcomers until relations were strained by continual immigration into their land, loss of resources, disease and other pressures.

Certainly there were cultural differences between Indians and non-Indians but in the beginning there was diplomacy, communication, and consideration. After time non-Indians began to take land the U.S. Government had offered that it did not own.

Initially the Tribes welcomed the newcomers but as the steady stream of emigrants arrived steady pressures on lands and resources began.

The Tribes were faced with people encroaching on their lands and enforced their laws as dictated through their traditions, and cultural practices. In some cases the Tribes actions were defensive and aggressive and non- Indians viewed this as hostile. The Tribes have always sought to live peacefully with their non-Indian neighbors only to be served a helping of injustice.

As immigrations began to increase, the Tribes heard rumors that government representatives were plotting to steal the homelands. The Donation Land Act of 1850, and territorial approval of settlers in the Columbia Plateau without regard to tribal consent, made for a pressure-packed situation. The American government was encouraging its citizens to move to the Oregon Territory. This was without first extinguishing the Indians' claims to their lands, and by depriving them of their usual and accustomed means of livelihood.

The United States made purchases and claims for vast portions of western North America. This was intended to alleviate the economic pressures in the East. Consideration was never given to the Native Americans already living there.

Treaties on the Plateau were an after thought when the Tribes provided a military obstacle and hazard to settlers. Treaties would be the tool to move all Indians to Reservations.

The execution of the Whitman's and the so called "native hostility" in the Columbia region clearly demonstrated the political and military control of the region. This was considered unstable by non-Indians wishing to settle in the area. As more and more non-Indians entered the country the mood became hostile and Indian uprisings and wars erupted in protest of this invasion. This made the fur traders, missionaries, settlers and the United States government uneasy. Eastern Oregon was essentially closed to non-Indians for a period of twelve years.

In 1851, the tribes negotiated with Anson Dart, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, whom wished to build a sawmill. Instead of a sawmill, the Utilla Indian Agency was built on the banks of the Umatilla River near present-day Echo, Oregon. This agency was burned down.

With the increasing influx of settlers, miners, soldiers and cattlemen, the tribes began planning to rid themselves of the intruders once again. In early 1853, plans were agreed upon by Kamiakin, of the more numerous Yakamas, as well as most of the interior tribes who had heard the rumors to displace them. Word was sent out by runners contacting other tribes in the northwest. Councils were met with tribes from northern California, Shoshone and Bannocks in Southern Idaho, and Flatheads of Montana.

Tribes on the Columbia Plateau were protective of their sovereignty and had elaborate warrior traditions and defended the people of the Plateau from their enemies. Due to the military strength of Tribes such as the Cayuse, Nez Perce, Palouse, and certain bands of the Yakama the United States began to meet with the Indian Tribes in the Northwest to negotiate and sign treaties in an attempt avoid further violence.

The primary purpose of the Treaty process with Indian Tribes from the United States perspective was to establish peace by removing the Indians from the land and to make way for industry and settlers. The unstable situation in Eastern Oregon was the product of the 1850 Oregon Donation Land Act. Emigrants were given land as an incentive to move out west but the political environment was not always safe.

By 1854, Governor Joel Palmer of Oregon had convinced the Indian Department that no further settlements were to be established east of the Cascades until the Indians there could be moved to reservations by treaty. By the end of July, Congress authorized negotiation of treaties in order to purchase the Indian lands, and establish a reservation for Indians.

Isaac Steven's then became Governor of the Washington Territories and had a program of action. Stevens' program of action included; settling Indian and foreign claims, conducting rapid surveys, provide adequate transportation, educational opportunities, and military protection for newly arriving emigrants.

On May 29, 1855, a Council was convened at the old Indian grounds on Mill Creek, six miles above Waiilatpu in the Walla Walla valley to discuss the situation in Eastern Oregon and to negotiate a treaty.

Officiating were Isaac I. Steven's, Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Washington Territory, and Joel Palmer, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Oregon Territory. They met with chiefs, delegates, and headmen from the Nez Perces, Cayuse, Walla Walla, Yakamas, and Palouses, with representatives of other Tribes present.

The events surrounding and the results of the Treaty Council of 1855 at Wai-i-lat-pu had profound impacts on the Columbia Plateau. The Treaty of June 9, 1855 between the United States and members of the Walla Walla, Cayuse, and Umatilla tribes was signed.

The Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Yakama Indian Reservation and the Nez Perce Reservations were created during these negotiations.

Originally Stevens and Palmer had planned on putting all the Indians in the region on the Yakama Indian Reservation. The treaty negotiations determined otherwise. The Umatilla, Walla Walla, and Cayuse tribes agreed to live on the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

The Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla had ceded 6.4 million acres to the United States and reserved rights for fishing, hunting, gathering foods and medicines, and pasturing livestock. They had also reserved 510,000 acres on which to live. The Treaty was subsequently ratified by Congress on March 8, 1859.

In negotiating such treaties Stevens, was successful in his drive toward opening up the Columbia River and the Washington Territory. The Indian people who traditionally lived along the rivers for a major part of the year were systematically removed sometimes by military force to the reservations. This was the actual beginning of non-Indian control of the land.

By 1858, the materially superior forces of the Americans had prevailed and most of the warring tribes were at peace. Because of the prolonged wars and conflicts with the United States the Indians were impoverished and greatly reduced in number. To make matters worse, the Shoshoneans begin to take advantage of the war-weakened Shahaptians of the region by constantly raiding for slaves and stock.

Going to the Reservation

The Federal Government forced the Indians onto the Umatilla Reservation and the ceded Indian territories were declared Public Domain and were auctioned at public sale, usually to land speculators and the railroads.

G. H. Abbott was given orders by the Indian Department and forced by the settlers, under threat of hanging Indians, to move the Cayuses, Umatillas and Walla Wallas to their reservation. By this time, many settlers had moved into the Walla Walla Valley and conflicts between the Indians and non-Indians was common place.

As for the Indians on the reservation, there were problems with ever-increasing immigration both east and west. Whiskey peddling, horse stealing, and other depredations by the outsiders were beginning to cause the superintendent of the Umatilla Agency many problems.

The transition to Reservation life was not easy but the Tribes had little choice. The Tribes and Bands at the Walla Walla Treaty Council were very close with family or traditional ties. Families and friends had to determine where and what reservation to live on. It was not an easy decision. The decision also meant a change in lifestyle. Instead of relying on each other Indians were taught the Christian work ethic and self sufficiency.

Many of the people went to raising gardens along the Umatilla in one-to five-acre lots. Trade continued with the non-Indians. The people still had many horses and were able to fish for salmon which were still the heart of their economy.

Leadership on the reservation was constantly challenged by the agents assigned in the early 1860's. The agents were charged with educating and civilizing the Indians. Conflicts arose when the agents did not use the chiefs and headmen, or when the agent directly supervised the people without the consent of the leaders.

Some of the elders have stated that agents refused to recognize traditional leader purposely because the treaty called for annual payments to the chiefs of the Tribes that the government representatives did not want to pay.

Children were educated by the Catholic or Protestant missionaries. Strict discipline was adhered to hair was cut, uniforms were worn, and children were punished for speaking their native language.

Some Indians refused to go live on the reservations. Homli and Smohalla were amongst those who refused to go to the reservations. They were concerned about their traditional ways, the old ways. They were not interested in the new God, farming, or new ways of life. They only wished to live by the unwritten traditional law.

Father Brouillett was replaced by Father Adolph Vermeersh a Belgian priest who rebuilt St. Anne's near the present government Campus in 1865. There was a turnover in the resident clergy and in 1883, St. Annes was moved to a site below Emigrant Hill and included a boarding school. The school was rare in that it was run by the Catholics under the direction of the government superintendent. A church was built in this location in 1884 and was named St. Joseph's. The sisters of Mercy operated the school until government officials began to interfere more and more. Finally the sisters closed the school in 1888 and opened a new one in Pendleton. The resident priest moved and was replaced.

Father Urban Grassi, SJ., arrived on July 8, 1888. He moved the St. Anne's mission to a more convenient location a quarter mile to the east and began the development of a school. Tutuilla Mission a Protestant mission was established in 1882 introduced by a Nez Perce Missionary. The black robed French Catholics and Protestants would have a lasting effect on the Tribes educating Indian children and ministering Catholicism. The Jesuits left in 1961 and the Baker Diocese took over management and a new St. Andrew's was dedicated in 1964.

The Reservation Boundaries were under attack even before it was surveyed. Public meetings were held in LaGrande, Pendleton, and Walla Walla by the late 1860's, to remove the Indians from the Umatilla Reservation.

The settlers had discovered that Indian lands were capable of producing wheat, and the mountains were good for livestock grazing. Roads and trails were utilized by the whites constantly encroaching on reservation lands. The settler's were in hopes of pushing the Tribes into another war, the objective being to extinguish the reservation.

The U.S. Government had agreed in the Treaty to move the Oregon Trail south of the Reservation to prevent problems. The establishment of a Reservation caused problems for non-Indians as well. There were restrictions and rules on the Reservation that were not elsewhere in the state. For example, there could be no alcohol on the Reservation.

The Tribes had reserved 510,000 acres for the Reservation in 1855. The actually surveyed Reservation totaled approximately 245,000 acres or approximately half of the Reservation reserved by Treaty.

Much of the debate arises over the location of "Lee's Encampment". Whether its location was in Meacham where the boundary was surveyed and the location where a Major Lee of the Oregon Militia once camped, or a place by Five Points Creek on the Grande Ronde where Jason Lee the Missionary once wintered, has never been resolved.

It is known that the town of Meacham near the summit of the Blue Mountains was a rest area for Oregon Trail travelers and was to be along the future railroad. The tavern and brothel at Meacham made a good deal of money serving a wide variety of refreshments.

The constant pressure of non-Indians on Indian land was great. Non-Indian encroachment of Tribal lands was causing many problems especially if the Indian land had any exploitable value to the non-Indian. In 1877 the lower Nez Perce went to war over their homelands after others renegotiated and sold their reservation lands out from under them because non-Indians had an interest in the land.

Members of the Cayuse Tribe frustrated at the changes and pressures brought by the United States fought with Joseph and his people in the Nez Perce War. Other Tribes such as the Yakama and Bannocks would also end up fighting against the injustice on non-Indians claiming their homelands.

Non-Indians desired to own lands on the Umatilla Indian Reservation that were seen as valuable agricultural lands. By 1878 in the "Annual Report" from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs it states in a discussion about the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Non-Indians were quick to point out that horses were impacting the environment. Basically, horses were preventing them from wheat farming on the reservation. The agent reported:

"The rapid settling of that portion of the state has surrounded the reservation with white farming population, who have already run across it a telegraph-line and several roads. The route of the Blue Mountain and Columbia River Railroad line transverses the southern portion, and the junction of the road with a proposed branch line is to fall within reservation boundaries.

This valuable tract is occupied by only 1,000 Indians, who cultivate between two and three thousand acres, and use of so much of the remainder of their lands as is required to furnish range for their 22,000 head of stock.

For several years past the citizens of Oregon have made persistent effort to have these lands open to settlement, and several bills to that effect have been introduced in Congress. This desire, which, gains strength yearly, is well known to the Indians, and begets a feeling of restlessness and uncertainty decidedly unfavorable to their progress in civilization."

This encroachment was devastating to tribal culture and economic well being. As tribal people, they were horsemen and fishermen, and wealth was determined in terms of livestock particularly horses. Horses allowed Tribal members the means to travel to usual and accustomed resource procurement areas.

The Umatilla Reservation was prime for the grazing of horses and the natural resources were "extraordinarily rich". In fact, early Indian agents descriptions of the Umatilla Reservation described the grazing and grass resources as "without limit". "The horses and cattle are always in splendid condition, and scarcely need any care in winter as grazing is good all year rendering it a very popular as well as profitable business to raise stock."

As a result on continued pressure from non-Indian citizens, the US Congress enacted legislation in the late 1800s, which continued reducing the size of the Umatilla Reservation. The legislation created land allotments for the individual tribal members at that time, then proclaimed the remaining acres as surplus and opened it up for settlement by non-Indians.

As a result of these things, today the Umatilla Reservation is 172,882 acres, of which 52% is in Indian ownership and 48% is owned by non-Indians. We have a checkerboarded ownership pattern and non-Indians still own land and reside within the Umatilla Reservation.

Assimilating our people

By the 1870's, many government and non-government policies had been developed to subdue and eradicate the power of Indian Nations. Treaties were entered into for the purpose of physically controlling the Nations and for extinguishing the claims of Indians on their territory.

By the 1880's the 1855 Treaty and Reservation had been breached by non-Indians many times. The Walla Walla's were not paid for Peo Peo Mox Mox's land claim; the Oregon Trail was not moved south of the Reservation; the Reservation Boundary was mis-surveyed; the town of Pendleton was allocated 640 acres of the Reservation; and the railroad was making plans to come through the Reservation.

By direction of the Secretary of Interior, an Indian Agent arbitrarily drew a line and removed the southern reservation.

In 1885 the Slater Allotment Act was introduced and it turned into a prototype as a model for the sale of "surplus" Indian allotments. By 1887 the Dawes Allotment Act was in full swing and approximately 100,000 acres on the Umatilla Indian Reservation were allotted to non-Indians. Approximately 30,000 acres were put up for sale.

The goal was to acculturate tribal members by intermixing non-Indians amongst tribal members. By doing such Indian culture, religion, tradition, leadership and government would be destroyed and the Indians would enter the "American melting pot".

Most of this allotted land was inevitably used for agriculture, specifically wheat and livestock. Indian agents on the reservations were ordered to "educate and civilize" the Indians, which meant missionaries, schools, apprenticeships, farming, and the allotment of lands.

By 1890, Indian Treaty Lands in the United States had been reduced by half. The Umatilla Reservation, through the Allotment, or Dawes Act of 1887, was reduced from 245,699 acres to 158,000 acres.

Many "forced" fee patents were issued to individuals who were described as being "competent" by the agent and his "committee from town." Indians and "breeds" weren't often considered competent. Much of the 87,699 acres not allotted was purchased by land speculators, timber, or sheep industries.

With the influx of non-Indians came many new things and ideas that would affect the Columbia Basin. With the settlers came land ownership, fences, livestock, agriculture, and new species of plants some of which are now considered noxious weeds in the basin.

At the time, the Tribes began to take residence on the Umatilla Indian Reservation and non-Indians began to make the majority of decisions about the use and management of the environment.

The Railroad came through without really ever trying to meet any of the Tribes concerns. They already had their plans and railroad designs and were paid in subsidy from the United States to construct their projects. The Tribes had asked the railroad company to tie its new rail line into the grade the ran up Wildhorse Creek instead of coming out of Meacham Creek and heading down the Umatilla River.

The Tribes were concerned about child safety, livestock, land, water, and root fields. The railroad, the biggest business of the time, was only concerned with real estate and money. The Umatilla River and Meacham Creek were irreparably damaged by railroad construction efforts

With the arrival of the non-Indian came the western Euro-American system of government, religion, politics, legislation and economics. Legislation such as the railroad land grants and the allotment acts were developed that encouraged exclusively non-Indian interests.

The Indians whom had ceded lands to the United States with reserved rights were relegated to staying on the reservation and had to have permission to leave. They were prevented from accessing many of their traditional use areas.

During the historic period CTUIR lands were reduced from over 6.4 million acres to 158,000 acres. Allotment acts, incentives for railroads, miners, ranchers, and settlers led to increased pressure on lands significant to the Tribes and even the Reservation. The Tribes interests were mishandled by agents, congressmen, and agencies.

The situation was similar to the proverbial "fox guarding the hen house". The reflection is that the Tribes wealth was reduced from a status of relative wealth and well being to poverty as a direct consequence of actions and policies of the U.S. Government.

The 20th Century

The treaty and the next century would be a harsh introduction for the Tribes to paper laws, politics, money, and greed in the American capitalistic and democratic system.

Four decades after establishment of the reservation a number of Congressional Acts were passed. The Tribes started the Twentieth Century playing legislative catch-up trying to find out what had happened to our homelands. The Acts for the most part were land-based, punitive actions on the part of Congress to correct the failing Allotment Act of 1887. The correction was not to return lands, the failure was that the Allotment Acts failed to integrate Indians into American Society.

In 1891, the Leasing Act and subsequent amendments were implemented on the Umatilla Reservation. The passage of the Lease Act promptly placed the non-Indians in a situation whereby they could approach Indians on a one-to-one basis for control of Indian resources.

In Umatilla County political lobbies and groups were formed by local farmers and traders as early as 1900 to promote their interests on a legal avenue.

The Burke Act of May, 1906, authorized the Secretary of Interior to issue fee patents to Indians deemed "competent." This too, expanded the market for sale of Indian lands. Heirship Acts from 1902 to 1916 further authorized the Secretary to sell lands of Indians deemed competent or incompetent. Money received was held for a 25-year period.

Congress passed an Act on July 1, 1902, for the sale of 70,000 acres of timber and range land now allotted ("Surplus Treaty Boundary Lands").

Transactions with public and semi-public agencies were conducted during the early 1900's. Many of these transactions were based upon Article 10 of the 1855 Treaty, which specified creation of roads, easements, and rights-of-way for "public purposes."

During this time questions were being raised about the management and status of the Indians and reservations. There was discussion about the Wheeler Howard Act and other legislation being passed by non-Indians that supposedly "in the best interests" of the Tribes.

Everywhere you went Tribes were talking about the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). Indians enrolled from adjoining reservations were living on the Umatilla Indian Reservation. Some had inherited allotments and were living on them.

Issues were many the Reservation was fractionated, there were hunting and fishing issues, horse roundup issues, and legislative issues. At this time many older Indians still spoke French and Council was conducted in Nez Perce. Indians who attended meetings would contribute what ever they could to have representatives attend local, state and national meetings.

Nationally the conditions on reservation was very noticeable. The Miriam Report of 1928, was a comprehensive study of post-Congressional Acts and their impact upon the Indian communities. The result of the study indicated mismanagement of Indian affairs by Congress and recommended a change in policies. As a result of the 1928 Miriam Report, the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 was offered to the Umatilla Tribes as a reform of the Federal Government's Indian Policy.

At that time the reservation dwellers were satisfied with how the BIA handled all our affairs relying on their Trust responsibility and the success of getting lands returned to Trust. This system also allowed for the continuing to use the traditional way of family leaders meeting in Council.

Due to the efforts of Tribal members petitioning local officials and politicians in Washington D.C., lands not sold or surplused to non-Indians were taken off the market and were set aside and managed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The Tribal Council voted by a 2-to-1 margin not to accept the provisions of the Indian Reorganization Act. Tribal elders recall that farmers, ranchers, and merchants in the area vigorously opposed the Indian Reorganization Act. The non-Indians claimed that the concept of I.R.A. was communistic and would further erode the powers of the Council.

After ten more years of discussion the Tribes were able to have lands restored to the Reservation. The Johnson Creek Restoration Act of 1939, returned 14,140 acres of land to the Confederated Tribes. The 14,000 acres of 352,000 taken were returned to trust status through a series of Congressional actions aimed at improving the lot of Reservation Indians. World War II ended any appropriations to through this act.

Organizing our government

Goals were not being attained at a very fast rate under the current system if anything times were worse complicated by a depression and World Wars. The issues were becoming bigger and more complicated.

The Tribes were no longer satisfied with those agents charged with upholding the Treaty of 1855. For years since the Treaty, Indians had to continually fight to exercise their rights off the reservation and at usual and accustomed fishing locations.

The BIA had failed to uphold the Tribes treaty rights. Tribal members were arrested for exercising their rights, even after the courts reaffirmed their rights, often it was racism that prevented Tribal members from exercising treaty rights and cultural practices.

Fishwheels and canneries did extensive damage to the fisheries and often inhibited or prevented the Tribes ability to access the fish. Hydroelectric and reclamation dams were being developed on the Columbia River and tributaries were continually threatened by irrigation.

Ancient usual and accustomed fishing locations along the river were becoming lost or worse useless. In the case of the Umatilla River the salmon were made extinct by irrigation and reclamation efforts as early as 1914.

Canneries tried to exclusively take fish from the Tribes usual and accustomed fishing locations. Local communities were arresting Indians for fishing off the reservation or for "out of season" fishing. The CTUIR and other treaty Tribes had to spend resources reaffirming and educating non-Indians about their rights. These and other assaults on many of the treaty reserved resources crucial for Tribal survival necessitated the Tribes to become directly involved in a new way to manage affairs.

The BIA had continued to manage the Reservation but by the 1940's, the Tribal Council found itself in a dilemma due to the lack of authority to control outside interests, especially with regards to lands passing out of Indian ownership or other public and unclaimed lands where resources were being impacted.

Another concern of the Council was poor management and conservation practices of the non-Indian farmers and ranchers. Erosion of farm lands, poor logging practices and overgrazing were primary concerns. Projects such as roads were not being finished. Other projects like Bonneville Dam in 1939 were being completed threatening many Tribal resources.

Beginning in 1947, a committee of tribal members were authorized by the Tribal Council to begin researching ways in which the Tribes could attain more authority over their affairs. The committee sought Bureau of Indian Affairs assistance. At one Council a BIA employee and Nez Perce enrollee had talked about organizing under a constitution so we could have a Tribal government that could handle our tribal affairs like a business." He was a well respected veteran and he helped to work out the details.

In 1949, a Constitution and By-Laws were adopted by a very close majority vote of the Council with 9 votes being the "decisive factor." The establishment of the Constitution and By-Laws as the operating charter effectively brought to an end the power of the headsmen and recognized chiefs in the Tribal Council. From then on we have been the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, a confederation in the homeland of the Cayuse. The new leaders of the Tribes, the Board of Trustees, would be elected.

In 1949, a Constitution and By-Laws were adopted by a very close majority vote of the Council with 9 votes being the "decisive factor." The establishment of the Constitution and By-Laws as the operating charter effectively brought to an end the power of the headsmen and recognized chiefs in the Tribal Council. From then on we have been the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, a confederation in the homeland of the Cayuse. The new leaders of the Tribes, the Board of Trustees, would be elected.

Issues were pressing as usual. By-laws, which were unheard of before, had to be developed, membership determined, hunting and fishing rights issues addressed. There were land and housing issues. It was very complicated and the new CTUIR Board of Trustees needed advice.

In 1950, the first Board of Trustees began to identify ways in which they could improve the reservation and attend to the needs of the people. Financing for most tribal projects were attained through timber sales and other smaller sources of income.

The needs of the community increased with additional concerns being education, standard housing, and health care. The concept of economic development was established through tribal resolutions aimed at resource management in timber, range and farming.

In 1951, the Umatilla Tribes directed its attorney to file a claim for lands ceded to the U.S. Government at the signing of the Treaty of June 9, 1855. The Tribes contended that thousands of acres had been excluded from the Reservation, and damages from the loss of fish and eel runs in the Umatilla River were also to be addressed in the courts.

The Indian Claims Commission issued its final judgment in favor of the Confederated Tribes for an out-of-court settlement. This however was just the beginning of a long judicial process to address problems with the Treaty negotiations of 1855.

During 1953, the Tribe received $4,198,000 from the United States for the loss of fishing sties at Celilo, Oregon inundated by The Dalles Dam. All enrollees realized approximately $3,494.61 in per capita payments. At this time approximately 47% of the Umatilla enrollees lived off of the reservation. In addition the U.S. Army corps of engineers agreed to construct 400 acres of fishing access sites to replace the ones inundated.

Celilo Falls was inundated by The Dalles Dam in 1957 closing one of the Tribes greatest resources. The last Salmon Feast at Celilo was held that year. Other dams like John Day, McNary and the projects on the Snake River decimated the fisheries.

Unemployment was very high at 60+%. The Tribes were looking for opportunities to get Tribal members to work. The Tribes were able to have the McNary townsite with all the trimmings of a golf course, trailer manufacturing factory, and post office turned over to the Tribes through the GSA process. The Tribes negotiated with S&S Steel to set up a factory there. There were homes for workers and everything needed there. The product was 55' house trailers. Tribal members were hired and quality products were produced. It went well until mismanagement after the dispute resolution process the steel company got the town.

In 1954, Congress enacted House Concurrent Resolution 108, known as the Termination Bill. This new threat to tribal survival was vigorously opposed by the Umatilla Tribes. Accompanying the Termination Bill was the notorious Public Law 83-280. P.L. 280's purpose was to place the people under the state government for criminal and civil jurisdiction including the maintenance of road systems which were turned over to the State and County Highway Departments, further alienating more trust land from the reservation. Public Law 280 was viewed by the Federal and State Governments as the initial in-road to terminating the reservation. Even though the Tribes were not terminated, P.L. 280 was official policy until 1990.

Feasibility studies were being conducted but most of the ideas required more resources than the CTUIR had readily available. The State of Oregon was helping the Tribe by poisoning the Umatilla River for sport fishing interests. More and more dams were being developed on the Columbia. Celilo was gone. New fishing sites needed to be constructed "In Lieu" of sites inundated by the dams. There was litigation and legal proceedings in the Indian Claims process.

A watchdog group of Tribal members known as "the Progressives" started meeting and discussing BOT management issues such as the McNary debacle and concerned about the BOT's future plans. The Progressives wanted to know how the leaders were going to address unemployment, housing, and future investments of the Tribes.

Around this time the CTUIR the BIA and the General Contractors Association began a training program on the south Reservation. The project was to create a dam on Jennings Creek on the lands restored to the Tribes. The intention was to create potential recreation development and an opportunity that would train Indian people and allow them to gain experience to go further in construction if they wanted. The lake was successfully completed and was dedicated to the Cayuse leader Hum-tipin who's band had lived in Walla Walla, Washington. This was small but needed success for the Reservation Community.

A turning point for the CTUIR was the final results and decisions of the CTUIR's claims heard before the Indian Claims Commission. The decisions addressed issues of aboriginal use and lands controlled, claimed, and compensated for by the Treaty negotiations.

The CTUIR had only been compensated for approximately 4.5 million acres as part of the 1855 Treaty Negotiations. The CTUIR Claim maintained that they in fact ceded 6.4 million acres. The country included lands in the John Day River Valley and lands in the Powder River Drainage. The CTUIR settled on the Claim and were compensated.

The Board of Trustees Program Planning Committee adopted a preliminary plan for the development of the Reservation's human and natural resources in September 1967. At the same time, issue groups were meeting on and off the reservation. Some of them had intentions of lobbying against the Board of Trustees' plan in favor of full per capita payments. Some were meeting to support plans for the reservation development and partial per capita payments.

On December 11, 1967, and March 30, 1968, Tribal members attended General Council meetings and overwhelmingly voted for the abandonment of the previous Board's programming plans and partial per capita payments. In August of 1968, a recall of the Board of Trustees occurred because the majority of the board members were in favor of programming the judgment funds. The majority of the new Board of Trustees proposed full per capita payments with the exception of $200,000 reserved for scholarships.

On October 29, 1969, a hearing was held before the Sub-Committee on Indian Affairs. As a result of the hearings, in which both sides of the controversy were heard, the sub-committee requested a referendum vote on disbursement of the funds.

On November 29, 1969, one month after testimony was given to the Interior subcommittee, the General Council voted by referendum on the disbursement of the judgment funds. The General Council voted for the full per capita payments with $200,000 set aside for scholarships. The 1970 per capita payments came in three separate payments.

As for the Board of Trustees, their goal, finally realized, they finally ended up with no tribal staff, and the tribal operating budget was completely exhausted. The General Council meetings, which at one time boasted 200 people per meeting, became inoperative for approximately one year due to a constant lack of quorum.

After 1970, the issues of claims and per capita payments had been settled. Tribal officials elected to office became heavily dependent upon non-elected members of the community for help and assistance since tribal coffers had been completely decimated during the 1968 and 1969 administrations.

In short, the Tribe was broke and completely disorganized. Anti-per capita factions began to pick up the pieces of tribal government which were still left intact. They relied heavily on the Program Planning Committee and Board of Trustees to program grants and contracts from the federal government.

Housing conditions were still poor, the community was swamped with alcoholism, and there were still no fish in the Umatilla River. Many Tribal members had moved as part of the Indian Relocation Program. Children were still being sent to boarding schools to learn trades. Members of the community quickly grasped onto the unfinished business of the 1967 Board of Trustees' Program Planning Committee. Eventually many of the planning committee projects were approved and funded with state and Federal grants.

Meanwhile, the Board of Trustees was attending to other government functions with a small, dedicated and over-worked staff under direction of the tribal executive secretary. Much of the tribal staff's operating budgets were B.I.A. financed contracts.

The damage to the fisheries resources and the many issues that revolve around a competitive fishery industry on the Columbia River led to the members of the CTUIR working with other lower Columbia River tribes. In 1972 the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Warm springs of Oregon, the Confederated Bands of the Yakama Indian Reservation, the Nez Perce Tribe of Idaho created the Columbia River Intertribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) to deal with major issues on the Columbia River as they affected treaty related fisheries.

The national mood toward the plight of the Indian nations was very receptive. The Johnson and Nixon administrations sought to assist the nations in their quest for human and economic self-sufficiency.

Indian governments were qualified to receive a myriad of federal assistance largely due to the Indian self-determination and Education Assistance Act of 1974. Credibility and accountability was demanded by the General Council and by the federal bureaucracy. The impact of federal dollars had both a positive and a negative influence. In order to get the necessary dollars, the Tribe sometimes had to compromise it's plans and priorities to become eligible.

At the tribal level, federal agencies have been know to politic right along with various issue groups on the reservations, causing further disorganization, creating autonomous tribal groups which became dependent upon the agency. Tribal affairs and leadership in days gone by was carried out through the chiefs and headmen, they were truly leaders, and must be credited with negotiating for the survival of the people. Survival is different today but no less difficult.

As for the people of the Reservation, in the social sense, every Indian individual has a responsibility to uphold the values and attitudes of the Tribes. A strategy was initially developed through the 1979 Comprehensive Plan to guide growth and development and to exercise the sovereign powers of Tribal government.

Self-determination at work

The 1980's and 1990's can be characterized as the visible beginnings and presence of self-determination efforts on the Umatilla Reservation. During this time there has been a substantial growth in tribal programs, services, enterprises and building and capital improvements. Many of the planning initiatives and dreams of the 1960's and 1970's have become reality.

The number of HUD-assisted Indian housing units has almost doubled from 125 to 245. The number of tribal employees has grown to nearly 1,100. Tribal enrollment grew to just over 2,300 by the end of 2002. The Tribe's operating budget has steadily grown and was at $97 million in 2003.

Land acquisition and restoration of the Reservation is a priority. The land base of the Tribes has increased with the purchase of 2,400 acres in western Umatilla County and 8,700 acres in southeastern Washington, as well as other smaller tracks on the Reservation.

In 1992 the Board of Trustees accepted a broad-reaching Tribal-wide reorganization plan that established a departmental setting for tribal programs to be supervised by an Executive Director under the policy direction of the Board of Trustees.

In 1994 the Plan was made effective with the strategic clustering of 15,000 square feet of new modular office and meeting space. Plans are underway for a Capitol building, which will eventually house most all the CTUIR departments and programs.

Some impressive progress, however, towards obtaining self-sufficiency has been several successful economic development initiatives including the Wildhorse Casino which employs nearly 400 persons. The Casino is part of a destination resort that includes a 100-room hotel, 100-space RV park, 18-hole golf course, and the Tamastslikt Cultural Institute.

An important success the CTUIR has had in establishing self sufficiency has been the establishment of an active and aggressive Department of Natural Resources. This department has evolved as a vehicle for providing an avenue for the Tribes to work directly with land managers to protect and enhance natural and cultural resources. A key accomplishment in natural resources is the restoration of salmon to the Umatilla river after 70 years of extinction.

The Tribes have contracted for, or assumed, a number of important economic, environmental, social and community programs that were provided before by the B.I.A. or by other local, state and Federal agencies.

Language is becoming more and more precious with fewer and fewer speakers. Schools and language curriculums are being developed and a program is under way to preserve the native languages.

The Tribes are working to form partnerships to find ways to creatively educate, train, and prepare Indian youth and young adults for the future.

Today the CTUIR is taking a more active role in directly managing our own health care. Poor water quality, pesticides, no fish, and changes in traditional diet to commodities has affected the health of the tribes. One hundred and fifty years of alcoholism, drug abuse, diabetes and high cholesterol introduced by the non-Indian world has also weakened and hurt the people. The health of the Indian people is the future and we need to care for our family using western medicine and traditional beliefs to heal ourselves.

The Tribes are heading into the 21st Century and are poised with the organizational leadership and confidence, professional, technical, legal, and economic resources to achieve a sustainable economy and cultural identity through self-determination.

Language

The three tribes (Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla) are part of a much larger culture group called the Plateau Culture. The Plateau Culture includes the Nez Perce bands of Idaho and Washington, the Yakama bands of Central Washington and the Wasco and Warm Springs bands of North Central Oregon on the lower Columbia River. There were many other smaller bands and groups such as the Palouse and Wanapum.

This large body of people belonged to the Sahaptin Language group and each tribe spoke a distinct and separate dialect of Sahaptin. The Umatilla and Walla Walla each spoke their own separate dialect, while the Cayuse in later years spoke a dialect of the Nez Perce with whom they associated a great deal. The original Cayuse language, which is extinct today but for a few words spoken by a few individuals on the Umatilla Reservation, is closely related to the Mollala Indian language of the Oregon Cascade Mountains.

Over the decades, our native languages have gradually been lost as the primary means of communication. Only a handful of our tribal members are fluent. In an effort to restore and retain our native languages, we have implemented a language program through our Education Department. Some of our elders are now teaching the languages to the younger generations.

Traditions

Many things we do every day are based on tradition, but in many ways, modern life on the reservation is much like modern life any where in the United States. People live in houses, drive cars, work at jobs and children go to public schools. The people speak English, have T.V.'s and eat many of the same foods that other Americans eat. But there are things that make the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Indian people different from other people.

Many things we do every day are based on tradition, but in many ways, modern life on the reservation is much like modern life any where in the United States. People live in houses, drive cars, work at jobs and children go to public schools. The people speak English, have T.V.'s and eat many of the same foods that other Americans eat. But there are things that make the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Indian people different from other people.

The Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Indian people have a culture or way of life that has been handed down to them by their parents, grandparents and great grandparents. The Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Wallas' each have their own language and traditions.

Grandparents, mothers and fathers teach their children and grandchildren how to hunt, fish, dig roots, make teepees and put them up, how to dance and sing Indian songs. All these are traditions of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla peoples. A hundred and fifty years ago, the Indians had to learn many of these things to stay alive. Today they do many of these because it is important to them not to forget the ways of their parents and grandparents.

When traditions are strong, they change very slowly. Many of the traditional ways of life are taught and practiced the same way today as they were before the non-Indians brought their way of life to this part of the country. A celebration honoring the traditional foods, called Root Feast, is one tradition that continues each spring.

Life cycle and Foods

Until the early 1900s, the culture of the Cayuse, Umatilla and Walla Walla Indians was based on a yearly cycle of travel from hunting camps to fishing spots to celebration and trading camps and so on.

The three tribes spent most of their time in the area which is now northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. They had lived in the Columbia River Region for more than 10,000 years. There were no buffalo in this area. The most plentiful foods were salmon, roots, berries, deer and elk. Each of these foods could be found in different places and each was available in different seasons. This meant that the Indian people had to move from place to place from season to season to their food and prepare it to be eaten and to be saved for the winter. They followed the same course from year to year in a large circle from the lowlands along the Columbia River to the highlands in the Blue Mountains.

In the spring the tribes gathered along the Columbia River at places like Celilo Falls to fish for salmon and trade goods with other tribes. They dried the salmon and stored it for later use. In late spring and early summer they traveled from the Columbia to the foot hills of the Blue Mountains to dig for roots which they also dried. In late summer they traveled to the upper mountains to pick berries and to hunt for deer and elk. In the fall the tribe would return to the lower valleys and along the Columbia River again to catch the fall salmon run. All would stay in winter camps in the low regions until spring when the whole cycle would start all over again.