CTUIR is excited to implement the Nixyaawii, Don’t Throw It Away! Project to address food waste and strengthen materials management for our Tribal community!

Our project focus is on post-consumer food waste: food waste that comes at the very end of the food system, in community prep and home kitchens primarily. This means the food left over on your plate at the end of a meal, food that has spoiled in your fridge, and scraps from meal preparation, all of which end up in the landfill unless intentionally diverted elsewhere.

This food waste has a tremendous potential to be part of the solution, instead of contributing to the problem of the climate crisis as it currently does. This project aims to address some of the barriers that currently exist to transition our community towards being part of the solution, and respecting our living and non-living relatives better in the way we manage our materials. You will find detailed information about the project and its activities at the pages below.

Goals of the Project

1. Food Waste Assessment

2. Community Capacity for Materials Management

3. Research/demonstration of the Áq̓paš

We are hosting various events for the Tribal community and regional partners to learn more about the outcomes of the project, as well as build skills and knowledge related to composting, recycling, repair and reuse, and other approaches to reducing waste created by our community. Many of these events are open to everyone, and some require registration so we can make sure participants are compensated for their time. Please contact the First Foods Policy Program at FirstFoods@CTUIR.org or (541) 429 – 7247 with questions or to register for any of our events!

Notice to the community: Project Utility Shed is now placed at the Nixyaawii Longhouse as of the morning of Wednesday Jan 15th! We are excited to reach this milestone and the community is welcome to learn more about why we placed this shed and what's in it! Thank you to CTUIR Public Works and Planning for their coordination and patience with us through this process.

Staff from CTUIR’s Planning, Public Works, and DNR First Foods Policy Program stand with Biowaste Technology and observe as the project utility shed is moved into place at its new home next to the Mission Longhouse (Jan 15 2025).

Staff from CTUIR’s Planning, Public Works, and DNR First Foods Policy Program stand with Biowaste Technology and observe as the project utility shed is moved into place at its new home next to the Mission Longhouse (Jan 15 2025).

The project utility shed that will house the Áq̓paš is lowered into place to be installed next to the Mission Longhouse (Jan 15 2025).

DeArcie Abraham of Biowaste Technology stands inside the new project utility shed and looks at the instruction manual for the Áq̓paš that will be set up and housed in the building next to the Mission Longhouse (Jan 15 2025).

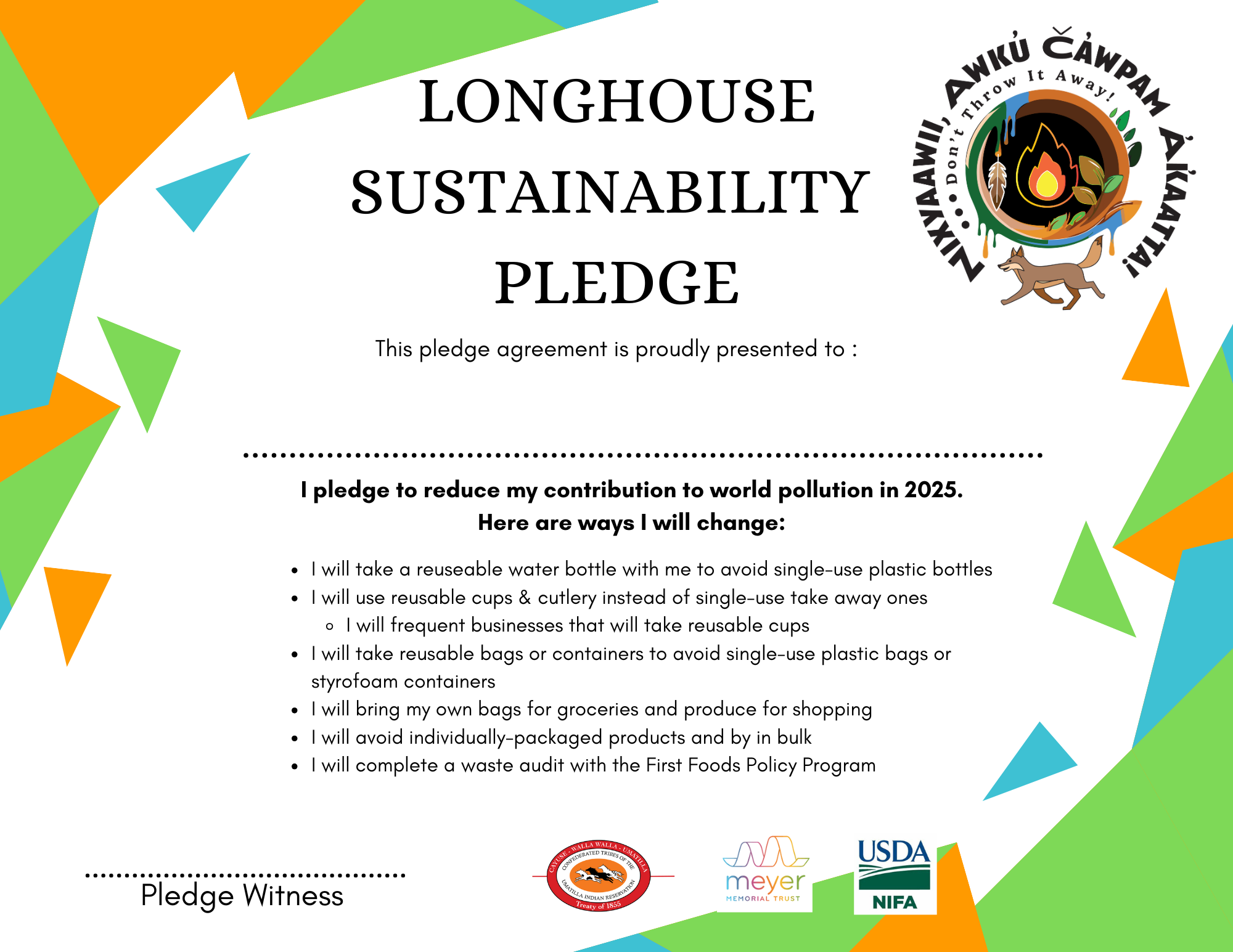

During the month of January 2025, our project will be asking our community take our Longhouse Sustainability Pledge! Keep your eyes out for times when we will be at the Nixyaawii Governance Center and Nicht-Yow-Way Seniors Center with those pledges, and get prizes for committing to reduce world pollution this new year!

Help us reduce food waste and single use plastic in 2025! Take our Longhouse Sustainability Pledge and commit to reducing your contribution to world polluiton in the new year

Initial Project Reception

State Interest

Oregon Public Broadcasting wrote a wonderful story about our project launch, please read that story here:

Umatilla tribes to launch food waste reduction project in northeast Oregon reservation - OPB

National Recognition

The Nixyaawii, Don't Throw It Away! Project is also honored to have been nominated by the Harvard Kennedy School's Project on Indigenous Governance and Development for their 2025 Honoring Nations Award! We are grateful to Harvard for recognizing the potential of this project and look forward to submitting an application to the award in the future.

Past CTUIR projects that have received this award include DNR Cultural Resources Protection Program (2003), CTUIR Homeownership: Financial, Credit & Consumer Protection Program (2006), Kayak Public Transit Program (2010), and Čáw Pawá Láakni - They Are Not Forgotten (Place Names Atlas) (2016).

Please read more about Harvard's Honoring Nations Award here: Project on Indigenous Governance and Development

Past Presentations

We are ALWAYS excited to talk about our project with anyone interested! We will archive past presentations here on this page, and link to any recordings available. Please find those past presentations below in the downloadable materials.

Funding Agency Disclaimers

This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, under agreement number 2024-70510-41990.

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. In addition, any reference to specific brands or types of products or services does not constitute or imply an endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture for those products or services.

USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer, and lender.

Webpage updated: Jan 7 2025